The illegal press

Public morale

Illegal newspapers published news about the course of the war and were important for public morale. They challenged German propaganda and incited people to resist. During the last year of the occupation they also printed many articles about the future of the Netherlands after the war.

Paula Joachimsthal

Paula Joachimsthal a school student from Amsterdam says:

'In the legal newspapers there was nothing but propaganda; the Germans won just about everything there was to win. Reading the illegal newspapers was important to the course of the war. It gave you strength. I got Trouw from someone living in my street, and Het Parool was delivered to the door. My father, being Jewish, refused to have anything to do with it. He was afraid. That's why we read the newspapers on the sly.'

Jan Wijnbergen

Jan Wijnbergen was a window cleaner in Amsterdam:

'The illegal newspapers contained reports of attacks, and why the attacks had been carried out. That was important to keep public opinion from turning against the resistance, because naturally German propaganda did nothing but portray those who carried out attacks as criminals.'

1.300

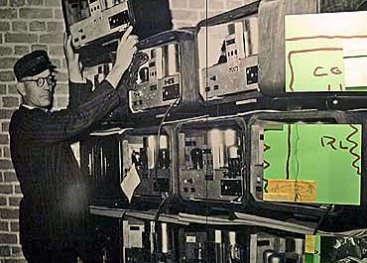

A total of 1,300 different illegal newspapers were published. There were many local editions, and all political and religious groups had their own paper. Circulations differed widely. Some of the papers were typed and stencilled in people's living rooms and distributed within the neighbourhood.

Most of the large national illegal newspapers such as Het Parool, Vrij Nederland, De Waarheid, Trouw and Ons Volk [‘The Motto’, ‘Free Netherlands’, ‘Truth’, ‘Faith’ and ‘Our People’] were ultimately printed on presses. These papers had a large network of people at their disposal who gathered the news and organised distribution.

![The printers’ inventory in the museum came from Jesse Printers in Amsterdam, where the underground newspaper Het Parool was produced. The big press was used to print De Vonk [The Spark] in Haarlem.](https://www.verzetsmuseum.org/media/cache/content_item_image/media/tentoonstellingen/verzetsmuseum_vaste_opstelling__lt_2021/merijnsoeters-0657-2.jpg)

Briefcase and stereotypes

By using printing plates, or stereotypes, instead of loose type, an underground newspaper could be printed at several different places throughout the country. The heavy plates were difficult to transport, so a cardboard print was made and used to create a new stereotype at the site.

Student Wim Speelman

Student Wim Speelman played an important role in the organisation of two illegal newspapers, Vrij Nederland and Trouw. The Sicherheitsdienst [German secret police] apparently knew his identity. In 1944, the SD promised to spare the lives of 23 Trouw employees who had been sentenced to death if Trouw ceased publication. Speelman only had to sign a note.

It was a weighty decision. But, reasoned Speelman, if he gave in it would be a stab in the back of every Dutch person who had been incited to resistance by Trouw. 'Keep going,' he decided. The 23 death sentences were carried out. Six months later Speelman was also arrested and shot.

Anton de Kom

Anton de Kom was a self-assured black man from Surinam who had fought for a free Surinam during the thirties. He also campaigned amongst the unemployed. As a left-wing activist he was exiled to the Netherlandshe and soon became involved in the resistance during the occupation and joined the permanent staff of illegal newspaper De Vonk.

On August 7th, 1944 De Kom was arrested in the street. The police found incriminating material in his briefcase. De Kom was subsequently imprisoned in various concentration camps: Vught, Oranienburg and Neuengamme. He was forced to do hard labour in the Heinkel aircraft factory. On April 24th 1945, just before the liberation, De Kom was deported and taken to Camp Sandbostel, where he died.