The hunger winter

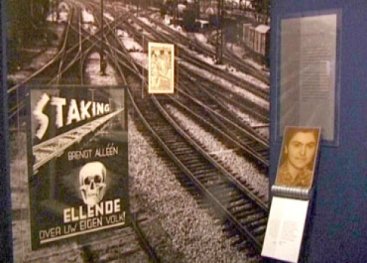

Railway strike

In response to the railway strike, food transports to the western Netherlands were banned. After six weeks the ban was withdrawn, but the supply remained frozen because of the dismantled railway network and the German requisitioning of goods. During the harsh winter of 1944/45, the socalled hungerwinter, there were severe food shortages in the cities.

Fuel shortage

The transport of coal from the liberated south also ceased. Gas and electricity were shut off. People chopped down trees and dismantled empty houses to get fuel. The amount of food available on ration dropped steadily.

Hunger expeditions

City dwellers went on hunger expeditions to the countryside. They traded their valuables with the farmers for food. More than 20,000 people died of starvation.

'My linens, all my silverware, my carpet, a Smyrna stair-carpet — I traded everything for food. In the long run the farmers wouldn't accept any more linen goods. Some of them even put up signs that said, "No more linen goods".'

Initiatives

Various initiatives were taken to deal with the severe food shortages. The churches of the northern and eastern Netherlands together found lodgings for 50,000 malnourished children from the cities. At the end of January 1945, the Red Cross imported flour by ship from Sweden. It would be another month before the legendary Swedish white bread could be distributed.

In April, Allied planes dropped food parcels over the Netherlands with the permission of the Germans. On May 2nd, Allied lorries carrying food were also allowed in. But organising a fair distribution was not easy. Most of the food could not be distributed until after the liberation.

An Amsterdam resident wrote:

‘… today again the engines of the heavy bombers could be heard over a jubilant Amsterdam. When will this food be distributed? A start has already been made on handing out the items from parcels damaged after they were dropped. For the moment, 7,000 parcels have been distributed among those suffering from hunger oedema.’

'There used to be a Crisis Controle Dienst [CCD, Crisis Control Service]. They'd stand at bridges and confiscate things. Whenever they'd show up someplace the news spread like wildfire. Then you'd have to go by another road. Many people on hunger expedition would complain about the mean farmers. It never occurred to them that they might have been number two thousand and that the farmers had nothing to give anymore.'

Potatoes by post

Small box of potatoes sent to the Bontekoe family. Daughter Anneke can still clearly remember the hunger.

'Fortunately our relatives in Groningen occasionally sent us boxes of potatoes by post. We had heard that you could save up the peels, take them to the farmers and trade them for milk for example. But when my father went to a farmer with the peels, the farmer claimed they were rotten.'