Help?

No, sorry, that's not my problem... I won't even think about that

Difficult decision

It was not easy to hide people in the densely populated country. The German authorities acted harshly against the practice. Very few Dutch people offered help. If you ring a doorbell at the exhibition, you can hear (a reconstruction of) the reasons:

‘For one night? No, we can't. My husband is too frightened. He recently had to report to the 'Sicherheitsdienst' (The German Security service, ed.) because he hadn't been courteous in helping a German officer. It terrified him. No, we're too scared; we don't dare. I don't know what you should do, but you can't stay here.’

...What you're doing is wonderful and I'd really like to help... but it's dangerous. And my life is just as valuable as that of someone in hiding, isn't it? I don't think I'll get involved after all... Sorry...

Truus van der Zwaag

Truus van der Zwaag was a seamstress at a sewing shop in Amsterdam. She says:

'I didn't believe the stories that you heard about what was happening to the Jews. It was so terrible that it couldn't be true. But afterwards we discovered that even the worst stories didn't come close to what was really happening. I didn't do anything. To really do somethig you had to have lots of courage. I wasn't very brave.'

Miep Roestenburg

‘I lived in a Jewish neighbourhood. I tried to help as many people as possible. They could always come stay with me for one or two nights. Those roundups were terrible, but it made you tough as well. I mean, what do you say to people when they're taken off? You hug them and wish them well. What more can you do?'

Miep Roestenburg, owner of a chemist's:

The Hollandsche Schouwburg on Plantage Middenlaan was the collection point for the deportation of the Jews. The young children were placed in a nursery across the road. It was relatively easy to find hiding places for young children. Various resistance groups managed to smuggle a total of 600 Jewish children out of the nursery.

Walter Süskind

Walter Süskind, a staff member of the Jewish Council, supervised the course of events in the Hollandse Schouwburg. He was on familiar terms with the German guards. Sometimes he even got them drunk. This enabled him to rescue about 2,000 prisoners from the Schouwburg and the nursery. He and his assistant Felix Halverstadt changed the information in the card system.

When a group was scheduled for transport, Süskind distracted the SS guards so they missed hearing Halverstadt count off the 'departing': 182, 183, 184, 195, 196... This could save the lives of ten people. Süskind himself died in the evacuation of Auschwitz in 1945. His wife, daughter, mother and mother-in-law had been gassed there a few months before.

Semmy and Joop Woortman

Semmy and Joop Woortman (assumed name: Theo de Bruin), a married couple, rescued Jewish children from the nursery.

Semmy recalls:

'It was difficult to just walk out of the nursery with children because on the other side of the street there were soldiers on guard in front of the Hollandse Schouwburg. But the head nurse at the nursery, Virrie Cohen, would stand in front of the door and tell us if tram 9 was coming.

We'd walk out of the door each carrying a baby under our arm. We'd run alongside the tram down the Plantage Middenlaan and at the next tram stop we'd get in, huffing and puffing. And all the people in the tram would start laughing because naturally they'd seen us, but they never said anything. Well, that's typically Amsterdam for you...'

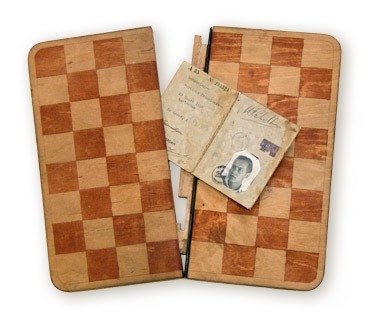

Chessboard

A hollow chessboard used by the Westerweel group to hide false documents. This mainly Jewish resistance group, set up by teacher Joop Westerweel, helped more than 150 Jews flee the Netherlands. Via an escape route, the Jews were subsequently helped on their way to Palestine.

Almost 25,000 Jews found a hiding place, but a third of them were nevertheless rounded up and killed.

The Levy family lived in Varsseveld in the Achterhoek.

On Christmas Eve 1941, they were visited by a member of the Dutch SS who turned out to be a school friend of their son Jonny. He warned them, 'Never go to work in Germany. There are camps there where the Jews are being murdered.'

‘From that moment’, Jonny remembers, 'my parents started looking for a possible hiding place — one for themselves and another for their three sons. When we were forced to move to Amsterdam on April 10th, 1943 the time had come to disappear.' The boys went to the farm of the Geurink family in Lichtenvoorde. An underground shelter had been built there for hiding. The entrance was in the pig pen, covered over with a lid.

Freddy Deen was eleven years old in 1943.

'The evening when the Germans came I was woken up. It was dark and my mother said, "We have to leave now. Tomorrow morning you go to the neighbours." I heard the doors of the police van close and I kept my head under the blankets. The next morning I went downstairs, scared to death. I went to the neighbours through the back garden. (...)

I was taken to a total stranger. He took me by bus to the Bogaard brothers in Haarlemmermeer.' I wasn't alone. Greetje was there, a friend from school, and many others also in hiding. We slept in the attic. I still remember Greetje lying awake and crying. But I wouldn't let myself cry. I lay flat on my back with my fists clenched. A kind of stupor...'